CAPTAIN WILLIAM “THE TORY” DEATON

Robert Curtis

Enjoy our stories?

Join our Readers List for updates.

SHORT BIO:

Robert F. Curtis gained entry into the Army’s Warrant Officer Candidate program where he learned to fly, starting him on the path to a military career as an aviator in the Army, National Guard, and Marine Corps, and as an exchange officer with the British Royal Navy. After service in Vietnam he attended the University of Kentucky, graduating with honors with a bachelor’s degree in political science. Later, while serving at Naval Air Systems Command in Washington, D.C., Robert completed a master’s degree in procurement and acquisition management at Webster University. Robert is an FAA certified commercial pilot in both helicopters and gyroplanes. His military awards include the Distinguished Flying Cross, Bronze Star, Purple Heart, and twenty-three Air Medals

Captain William “The Tory” Deaton

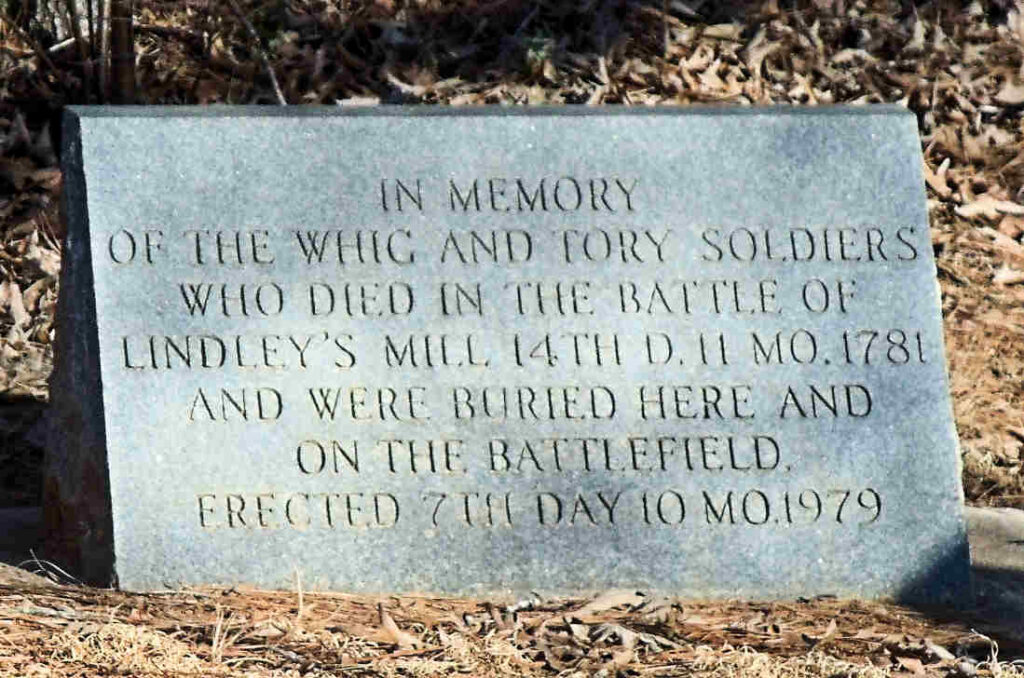

My sixth great grandfather lies in an unmarked grave somewhere on the battlefield of Lindley’s Mill, North Carolina, where he died on September 13, 1781. Unlike most battles, this one had no clear winner, both sides withdrawing after the bloody clash. No one on either side stayed on the field to bury their dead after the fight was over. Instead, the local Quakers, peaceful people that they are, gathered them up. Many were buried in two mass graves, but some were buried where they fell. Sadly, none of the burial sites were marked and in a short while all signs they laid there had disappeared, except for two shallow depressions that may or may not hold some of their bodies. No attempt was made to separate the Whig rebels from the Tories because none of the dead were wearing uniforms, and the Quakers didn’t know any of the men since they were from away. Both sides were militia and not regular soldiers, so they all died in the clothes they were wearing when they left from home. Enemies they were, but now they all rest together in their final peace.

This is the story his son, my fifth great grandfather might have told…

I, John Deaton, was 15 years old in 1781, just big enough to be a militia man myself and like my father and grandfather, I was loyal to King George III. Our family had been in the colonies since 1640 and had prospered as Englishmen here. Besides, we were staunch Church of England men, and the King was the head of the church. How could we fight against him? Father took it for granted that I would march to join him when his company went with Colonel Fannings regiment to attack Hendersonville and capture the rebel governor and as many Whigs as we could. After all, father was captain of our company, albeit only for less than two weeks.

I looked up to my father, but then everyone did since he was 6’6” tall, a literal giant of a man in those days. His eyes were like mine – an ice blue. He wasn’t afraid of anything, perhaps not the best trait in a war that pitted neighbor against neighbor. He had proved his courage at the Battle of Bettis’s Bridge only two weeks before the fatal fight at Lindley’s Mill. Although only a private soldier at Bettis’s Bridge, he led an assault that broke Colonel Thomas Wade’s Whig line, sending the rebels fleeing towards safety. The rebel force would have been completely destroyed had Colonel McNeill been able to get his blocking force into position in time, but the Whigs broke too soon and many managed to slip through before McNeill could meet them. Still, with a loss of only one man killed and four wounded at Bettis’s Bridge, Colonel Fanning’s Tory Loyalists captured 50 rebels and 250 horses, in addition to 24 Whig dead the Colonel counted on the battlefield. Father’s courage in this fight prompted Colonel Fanning to appoint him captain of a company, a proud moment indeed.

I was getting ready to depart our home on Bear Creek, a few miles southwest of Chapel Hill, North Carolina, when a neighbor rode in with news of our victory and father’s promotion. Eager to join him and take my place in his company, I took my hunting rifle and perhaps twenty rounds of ammunition, leaving a rifle and some powder and shot for the family. My 13-year-old brother Matthew would be the man of the family to protect our mother Mary and two younger brothers while father and I were away. I took some food and a blanket too, not knowing what things would be like when I joined the company. I didn’t take our remaining horse because the family would need her on the farm. Besides, walking 30 miles or so meant nothing to the 15-year-old me. Father’s company was then near Hillsborough, the colony’s capital so that was my destination.

After two days of walking, I arrived at Colonel Fanning’s camp. It wasn’t much of a camp because the regiment was constantly on the move. I asked one of the sentries where William Deaton’s company was and soon found myself reporting to father. But he wasn’t just my father, he was Captain Deaton now and I was just another private soldier. After a hard handshake and enquiries after the family, he directed me to report to Sergeant Jackson and follow such orders as he would give. I thought I might have seen a touch of pride in his eyes as I turned to go.

The sergeant looked me up and down when I reported. He saw a 6’2” tall boy who weighed perhaps 160 pounds and only needed to shave once a week, if that. He just shook his head and frowned but motioned me to follow him. Still, I had brought my own weapon and ammunition so I would suffice. No mention was made that my father was the commander because there were other father and son soldiers here. All followed the orders of the chain of command with no favoritism expected or given. I found a place to sit down as some of the men cooked a stew in an iron pot over a fire. I hoped I would be included in whatever meal they prepared since the food I brought from home was long gone. After the older men had been given theirs, I was given a bowl full of mostly water but at least it had some meat taste to it.

Father had disappeared to Colonel Fanning’s tent to receive orders for our next attack. One of the men told me he thought we were going to take Hillsborough with the possibility of capturing the Whig governor and as many of his staff as we could. The ones we captured would be taken to Wilmington and turned over to the British regulars there. We would have a fight of it if the rebels knew what we had planned but somehow, I thought we might get away with it. The weather had been unseasonably chilly for the last week, with morning fog that lasted until ten or eleven. Even as young and inexperienced as I was, I saw that if the fog held, we could be upon them before they knew what was happening. Now if only their sentries were complacent because they were in the rebel capital…

Father came back and the older soldier’s thoughts were confirmed. We will march on Hillsborough tonight. Some men familiar with the local area will guide us. We were ordered to be as silent as possible when we approached the town to surprise them. It being early afternoon, most of the older men immediately lay down to take a nap. I was too excited to actually sleep, but picked a spot under a tree and pretended. I wanted to show that I too was experienced enough to know that a full rest might be a long time coming.

About midnight we started to move. The road was smooth enough for an easy walk. We arrived at the town and spread out around it. At 7 o’clock in the morning we moved forward towards the houses. All the while we were expecting the guards to give an alarm, but they must have been sleeping because no one raised a cry until we were in position. In the fighting 15 Whig rebels were killed, but I didn’t fire my rifle as I didn’t see anyone to shoot at. When it was over we had captured Governor Burke, most of his staff, and around 150 rebel militia before they really knew what was happening. Some of our men, wanting revenge for Whig actions in the past began looting some of the houses, taking what they would and despoiling the rest. I was shocked at this and knew that certain of the Whigs would take their own revenge in time.

Colonel Fanning ordered us to take the nearly 200 prisoners down the Wilmington Pike so that we could turn them over to the British regulars garrisoned there. We left Hillsborough around noon, marching down the road in a column of twos with several companies in the lead, the prisoners in the center, and the remainder of our forces bringing up the rear. An hour before dark we ended our 18-mile march and set up camp. We shared our food and water with the prisoners, never mind most of it was looted from their town. The excitement of my first battle, small though it was, had worn off and I was by then exhausted. My day was not over because my sergeant ordered me to help guard the prisoners. I finally was relieved and managed to go to sleep around two in the morning.

Not long after dawn we were marching again, still headed to Wilmington. By noon we were approaching Linley’s Flour Mill on Cane Creek. Father’s company had moved up to the front of our column. I was back with him now, no longer guarding the prisoners but marching alongside the sergeant. Sergeant Jackson started to speak to me but there was the sudden crack of a rifle and he fell backwards, chest shattered. Ambush! We were under attack by the Whigs.

Where were they? Where were they? We started seeing flashes and smoke from the other side of Cane Creek, up a hill a little way. Father was yelling orders, but I didn’t understand them between wounded men screaming and the rifle fire from both sides. I got behind a log and fired blindly towards the attackers on the little hill above us. I wasn’t very quick about reloading, maybe two shots a minute was all I could manage in calm times but now I was lucky to get two shots out in three minutes. Not that it mattered – I couldn’t see anyone to shoot at, just smoke on the hill up above us. After about four shots I remembered that I only had enough ball and powder for perhaps 20 shots when the fight started. Few of us Tories had military muskets, but instead had only the rifles and ammunition we brought from home.

A few minutes later Colonel Fanning came riding up and yelled for us to spread out in a line. We did and then some officer yelled for us to go forward so we all moved towards the hill in a ragged line. The firing from the Whigs had about stopped by then. So did ours because there was nothing to shoot at and everyone else, like me, had very limited ammunition. We all stopped and wondered what would happen next. The answer was nothing. For an hour we just sat there in the bushes. Father came along but he didn’t know any more than anyone else did. Then the order to attack came from Colonel Fanning and we left the bottom and started up the hill. There was more firing but again, we couldn’t see where it was coming from. Father disappeared into the smoke as we climbed the low hill. I never saw him again.

We got to the top of the hill but there were only a few dead men and two wounded Whigs there. Winded and nearly out of ammunition, we stopped to catch our breath. As we rested, I looked at one of the dead Whigs. I had seen death before but never had I seen violent death, not like this. The ball that killed the man had taken him full in the face. I choked, bile rising in my throat before I looked away. An officer I didn’t know came along our line ordering us back down the hill toward the road. As we moved back down the way we came, I looked for father, but he wasn’t among the disorderly column of men moving through the woods. Once on the road, we marched toward the Quaker meeting house half a mile away where our prisoners were.

Colonel Fanning was nowhere to be seen. One of the men told me that he had been badly wounded in the fight but was still in command. He was hurt too badly to leave the field and presumed that he would be captured when the Whig rebels returned. There were somewhere around 60 of our men hurt too badly to leave the field but others would have to care for them since we too were afraid the Whigs would return and take the rest of us. You can’t fight when you are out of ammunition and have no bayonets.

Then the order came to move the prisoners down the Wilmington Pike and away from the battlefield. The rebel Whigs didn’t come back and we were unmolested all the way to Wilmington. Once there we turned the prisoners over to the British regulars garrisoned in the town. All us militia men were released to return home. Father still hadn’t turned up. Hoping he was among the wounded and left on the battlefield, I resolved to find him before I returned home.

I walked back up the Wilmington Pike to Lindley’s Mill, hoping to find Father among the wounded but no one knew anything about him. I was surprised at that because his height made him a distinctive man The Quakers had cared for the wounded until either their people came for them or they died. They buried the dead from both sides in common graves. They had been neighbors before the war and would rest together near where they fell. After two days of searching I gave up and walked home. Mother was a tough woman, but Father’s death took a lot out of her. She left all decisions to me now that I was the head of the family at 15.

I was right about the Whigs seeking revenge. Our now American neighbors began harassing us at all turns short of actual violence. With the end of the war in September 1783 it got even worse, so we decided to sell and move away before the new government took our land by force. It was the same for all those who had fought with us in the Loyal militia. Many of them, including Colonel Fanning, left for Nova Scotia and others to England but we didn’t want to do that given the size and age of our family. Saving only our oxen and horses, we sold everything else for whatever price we could get and left for Kentucky, hoping that there that no one cared which side you were on in the late war. With brother James driving one wagon and me the other, we left North Carolina never to return. Father will always remain in his unmarked soldier’s grave at Lindley Mill on Cane Creek. I hope he rests easy there, grave unmarked but not forgotten.

*** end ***