LIEUTENANT GREENE AT HARPER’S FERRY

Robert Curtis

Enjoy our stories?

Join our Readers List for updates.

SHORT BIO:

Robert F. Curtis gained entry into the Army’s Warrant Officer Candidate program where he learned to fly, starting him on the path to a military career as an aviator in the Army, National Guard, and Marine Corps, and as an exchange officer with the British Royal Navy. After service in Vietnam he attended the University of Kentucky, graduating with honors with a bachelor’s degree in political science. Later, while serving at Naval Air Systems Command in Washington, D.C., Robert completed a master’s degree in procurement and acquisition management at Webster University. Robert is an FAA certified commercial pilot in both helicopters and gyroplanes. His military awards include the Distinguished Flying Cross, Bronze Star, Purple Heart, and twenty-three Air Medals

Lieutenant Greene at Harper’s Ferry

Copyright Robert Curtis 2024

My name is Greene, Israel Green, late Lieutenant of United States Marines and late Major of Confederate States Marines, now a retired civil engineer and farmer here in windswept Mitchell, South Dakota. It is an honor to address the Davison County Historical Society on the fortieth anniversary of the end of the War Between the States. Now in 1905, 1865 seems so far away but like so many old soldiers from that war even though my military adventures are long past, I remember them as if they were just yesterday. One in particular often comes to mind – the time in 1859 when I captured John Brown at Harper’s Ferry.

I was born in Plattsburgh, New York but grew up in Wisconsin when my family moved there to follow my father’s employment. As a boy I dreamed of being a soldier and read of the great battles of the past. At the same time, I dreamed of the sea, a contradiction with being a soldier, or so I thought. Then I discovered the Marines, the “soldiers of the sea”. As soon as I had finished school I applied to join and after considering my engineering educational background, I was commissioned a Second Lieutenant of Marines on March 3, 1847. It was one of my proudest moments.

Promotions were very slow back then so when I was assigned to the Marine Barracks Washington, D.C. in 1857, I was still a first lieutenant. There were only a few Marines at the barracks, 90 in total. Most other Marines were deployed in Navy ships to ensure discipline and provide leadership when operations ashore demanded it. I was often the only line officer on duty at the Marine Corps Headquarters at 8th and I Streets since all the others were either on leave or deployed to various duties on ships in the Chesapeake Bay.

October 17th was a sleepy Sunday. It was then that I heard a rumor that John “Osawatomie” Brown, the mad abolitionist, had seized the arsenal at Harper’s Ferry. The rumor became fact the next day when Chief Clerk Walsh of the Navy Department personally came to see me to inquire about how many Marines were available for immediate action. I told him 90 and he rapidly disappeared in the direction of Naval Headquarters. An hour later, a message came ordering me to take all available Marines to Harper’s Ferry immediately. I was to bring food and weapons with sufficient ammunition for a week’s operations. A special train would leave from the Washington Station at 3:30 to transport us there.

In all my time in the Marine Corps I had yet to see combat, yet to command Marines in action. Now was the time. I thought, too bad it is against these puny insurrectionists and not a real military force. That said, Marines fight where and when they are told and my time to fight was now.

Calling my duty sergeant, I ordered all Marines into formation immediately. I ordered seven of them to stay back to maintain security in headquarters while we were deployed. All others were to change into dress uniforms, as specified in the War Department order, and report back in one hour. We weren’t going to fight pirates or foreign enemies, but internal enemies and I intended them to see that Marines had no fear of them whatsoever. In case they didn’t get the message, I ordered two Dahlgren artillery pieces and ammunition be sent to the station and be loaded onboard the train, just in case artillery was needed to reduce whatever works Brown was holding. One hour later, we were marching to the train station. At last, some action after the boredom of barracks life!

People on the streets cheered as we marched to the station, making my Marines even more resolute in their countenance, with their dark blue frock coats, sky blue trousers, and gleaming rifles. Marching with us was Major Russell, the pay master. He was a staff officer, not a line officer so he couldn’t command. Even so, he was a Marine and wanted to see what would happen when we reached Harper’s Ferry. In line with his staff duties, his only weapon was a small cane, commonly called a swagger stick. Confident that my Marines would dispatch any resistance quickly, I carried only the Mameluke sword, a light dress sword carried by all Marine officers.

The Baltimore and Ohio train was a short one, three passenger coaches and one baggage car. The baggage car held our two artillery pieces and the required food and ammunition. Rarely have I seen the speed at which the railroad men moved to prepare for our journey. We were scarcely on board when the train started to move. I thought we would go directly to Harper’s Ferry without pause but we were flagged down at Frederick Junction. There I was handed a telegram from Colonel Robert E. Lee, the commander of this expedition. We were to proceed to Sandy Hook, a mile or so short of Harper’s Ferry and await his arrival.

The train cars were comfortable so on arrival, rather than have my men wait outside I ordered them to remain onboard. Rested and fed Marines make the best fighters so we ate a light meal and dozed off. When you go into a fight you don’t know when you’ll get a chance to do either again so take advantage of all chances to do both. At about 10:00 p.m. Colonel Lee’s train pulled in. I should say, his engine pulled in. When his special train was ordered there were no passenger cars immediately available, so instead a single engine was dispatched. Colonel Lee and Lieutenant Stuart rode in the cab with the engineer and fireman as the engine traveled at top speed. When they arrived at Sandy Hook, they were both covered in soot from the engine.

My wife Edmonia’s family knew the Lees of Virginia quite well. Through her I had met Colonel Lee socially in Washington. I knew from his war record in the Mexican War he was indeed an excellent commander and I was honored to serve under him. In his haste to get to Harper’s Ferry after he had been summoned to the War Department, he had not gone back to his home in Arlington to change into a uniform and so was still in his civilian attire. With him was a Lieutenant that I didn’t know, one J.E.B. Stuart. It seems Lieutenant Stuart had been at the War Department trying to interest them in a new device he had invented for attaching a saber to a cavalryman’s belt when the news of Harper’s Ferry arrived. He volunteered to deliver the order for Colonel Lee to come to the War Department, from his home at Arlington House. After he delivered it, Lieutenant Stuart promptly volunteered to be the Colonel’s aide and was accepted.

I immediately reported to the Colonel, briefed him on what I had been able to learn from the Virginia and Maryland militia guarding the compound, and asked what his orders were. Considering for only a moment, Colonel Lee then ordered me to march my Marines to the arsenal grounds and take charge from the militia. I saluted and departed for the passenger cars holding my Marines. My sergeant had already formed the men and in a few moments, we were marching up the tracks and into the town.

The Virginia militia men holding the grounds around the pump house were all too happy to retire and turn the place over to us. They had been there for two days and were tired. It was near midnight when we arrived at the arsenal and the rain had started. It would rain all night but my Marines didn’t mind. The thought of the coming action kept them warm.

Brown, his men, and the hostages were holed up in a strong brick building that was the fire engine house on the arsenal. Entry was through two heavy, reinforced wooden doors. There was no other way out of the pumphouse, but I deployed my men in a manner to cover all sides anyway. Nothing was going to happen until the Colonel announced his plan so I ordered that half of the men should rest, with changes after every two hours. When everyone was posted, I left them and joined Colonel Lee and Lieutenant Stuart to discuss the plan of attack.

Colonel Lee was quite clear in that he wanted to make sure none of the hostages were hurt if at all possible. To that end, I proposed that my men go in with only bayonets instead of loaded muskets. Colonel Lee agreed. Lieutenant Stuart would present a written demand for immediate surrender and the instant they rejected the offer, the attack would begin.

The rain had stopped but there was no sun that morning, only gray mist. With daylight, the militia from both Maryland and Virginia returned. They again completely encircled the engine house and the area around it. I had drawn my men back and marched them in formation to the area right behind where Colonel Lee was observing the site of the coming battle. The sight of my Marines in their dress uniforms and with fixed bayonets was a sharp contrast to the raggedy semi-unforms worn by all else. It was obvious to all that we Marines were the elite professionals here. The people of the town had turned out to watch too. They hung from every window, trying to get the best view of what was to come. Some were even standing on top of the Baltimore and Ohio rail cars down the way.

Because Brown’s men had attacked in Maryland first, Colonel Lee offered Colonel Shriver of the Maryland militia the honor of attacking. Much to Colonel Lee’s displeasure, he declined on the grounds that his men might be injured. Flushing red in embarrassment, Colonel Lee turned to Colonel Baylor of the Virginia militia making the same offer. Colonel Baylor refused on the same grounds and suggested that the “mercenaries”, meaning we regular Marines, do it. Colonel Lee was appalled that two companies of militia declined to attack the five remaining insurrectionists. He considered it an offence against the honor of both States. He turned to me and asked me if I would take the honor ending Brown’s insurrection. I stopped myself from smiling and raised my hat in salute instead. This is why I joined the Marines.

The plan was simple. I would lead a party of 12 Marines as the attacking force, with another 12 standing by as reinforcements. Lieutenant Stuart would deliver an ultimatum demanding the release of the hostages and the surrender of Brown and his remaining men. If it was refused, Lieutenant Stuart would drop his hat as the signal for my Marines to attack. We would batter down the door with sledgehammers, proceed inside, capture all the insurgents, and free the hostages.

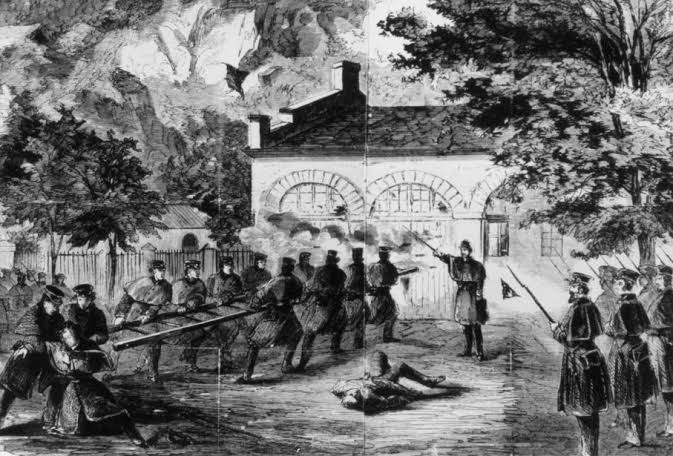

Lieutenant Stuart made quite a sight in his blue cavalry officer uniform, with spurs shining and his plumed hat in place as he walked up to the pumphouse door at 7:00 a.m. on October the 19th. He delivered Colonel Lee’s ultimatum. Brown tried to argue instead of surrendering so after about 30 seconds Lieutenant Stuart took off his hat and dropped it to his waist. In an instant three Marines were at the pumphouse door with their sledgehammers. From inside came a voice yelling, “Don’t mind us! Fire!”.

The wood cracked but Brown had used rope on the inside to keep it from opening. Seeing that the sledgehammers weren’t working, I ordered them to stop and instead pick up a large ladder and use it as a battering ram. On the second stroke the wooden door splintered and a hole big enough for a man to enter opened. At that moment Brown fired his Sharpe’s carbine through the door. A second after that shot, I was through the opening with my sword drawn and into the gloom of the interior of the engine house. Major Russell, armed with his cane was on my heels along with Private Luke Quinn. By then Brown got off a second round from his carbine, hitting Private Quinn in the belly, killing him.

One of the bravest men I have ever met was standing there in the semi-darkness. Colonel Lawrence Washington, great-grandnephew of President Washington. He calmly said, “Hello, Greene. That’s Osawatomie” as he pointed to the man directly in front of me. I knew the Colonel socially and even in the confusion of the attack, he remained collected enough to recognize me and point out my chief opponent. It had been he who was calling for us to fire as we hit the door with the sledgehammers.

Brown was trying to get another round into the chamber of his carbine but before he could act, I brought my sword down on his head. He was moving, so the blade mostly hit his coat collar but part of it landed on his neck, cutting him slightly and partially stunning him. He fell backwards with the blow. I then tried to run him through, but his thick belt caused my sword’s blade to bend. I hit him with it several more times and he became insensible.

My Marines had poured into the room right behind me. One of Brown’s men got off another shot, wounding Private Matthew Ruppert slightly in the face. That insurgent was promptly bayonetted to death, as was another with a rifle, on the ground, under the pump engine. At that point, resistance ceased and I ordered my Marines to hold everyone else captive. All the hostages were alive and uninjured as Colonel Lee desired.

From the time Lieutenant Stuart’s hat dropped until it was over was less than three minutes.

I sent the hostages out first. They were very tired, hungry, and dirty but glad to be alive. Colonel Washington was the last to leave. Ever a gentleman, he wiped his face with his handkerchief, straightened his clothing, put on his gloves so that the townspeople would not see his dirty hands, and walked out with a smile on his face. Tough men, the Washingtons.

As we carried the unconscious Brown and his surviving men out of the engine house, the militia and the townspeople were shouting, “Hang him! Shoot him!” but Colonel Lee was quite clear that Brown and the others would face justice, not a lynch mob. My Marines formed a protective circle around them and the sight of 80 Marines with grim faces and fixed bayonets stopped any thought of taking Brown. We took them all to the arsenal paymaster’s office so that their wounds could be tended and then placed a strong guard around the building.

The next day, I escorted Brown to Charles Town where he was turned over to civil authorities. Angry that he had killed one of my Marines and wounded another, I didn’t speak to him other than the words required to get him on the way. He seemed quite composed even knowing what awaited him.

I and my Marines were soon back in Washington and resumed our normal barracks duties. I did see John Brown one more time, that being the occasion of his hanging on December 2, 1859. I brought my Marines back to Charles Town as part of a force intended to prevent any attempted rescue of Brown. We stood at attention with the other infantry assembled for the occasion. Virginia Military Institute cadets, under the command of Major Thomas Jackson, later known as “Stonewall Jackson”, were there too. Another witness was a temporary member of the Richmond Grays Militia, an actor named John Wilkes Booth. I will give John Brown this – he went to his death like a man. His last words were in a clear voice and he did not tremble.

Two years later, when Virginia seceded from the Union. I was torn as to what to do. I resigned from the Marine Corps to consider my next move. Wisconsin offered me a commission as a colonel of volunteers and Virginia offered a commission as a lieutenant colonel of the Virginia Infantry. I found I could not fight against my adopted state of Virginia but at the same time I wanted to remain a “soldier of the sea”, so I enlisted as a captain in the Confederate Marine Corps. I remained as inspector of the Corps until at last I surrendered with General Lee at Appomattox. I found Virginia so changed after the war that my family and I moved west to our great state of South Dakota where I took up civil engineering and made a new life. I hope I have not been too windy this evening in sharing my story. Thank you for the honor of presenting it and goodnight.

*** end ***